Lisa just loves the greenmarket on Cortelyou Road. Every Sunday she returns with a report about how it has grown, or how busy it is. She presents the week’s trophy fruit or vegetable. This week Lisa said she’d purchased the most gorgeous fish. She called it a striper. I smirked. Nobody sells whole stripers at the greenmarket. Hours passed. Lisa worked intensely cleaning up after the painters. Howard Hall was more in the weeds than usual. The playroom ceiling had been replaced.

I did nothing. Worse than nothing, I played SPORE for the entire afternoon (I’d ordered the game when it first came out, but was only now trying it out. It’s completely absorbing).

The sun set. The kids argued. “So are you gonna cook this fish, or what?” demanded Lisa.

“Me?” shaking free from the care and feeding of my gayly painted two-legged carnivore with antlers, long, bony hands for grasping and nasty biting teeth. “I’m cooking the fish?”

“It’s too big for me to cook. And its got scales.”

“What is it?”

“I told you, a striper.”

“A bass? You mean a ‘sea bass.'”

“A striped bass.”

“Like this?” I asked, holding my hands seven inches apart.

“Much bigger.”

I held my hands nine inches apart. Lisa shook her head.

“A legal striped bass is 28 inches minimum.”

“At least.” Lisa nodded her head.

You bought a wild bass at the greenmarket? Not scaled? Is it gutted?”

“Nope,” said Lisa losing patience with my condescending questions. “The lady said it wasn’t hard to do.”

“It’s not, if you’ve done it a hundred times, but it’s always messy as hell.”

“Forget it!” Lisa stormed. “I thought it’d be fun. I’ll just throw it away. We’ll just have chicken fingers.”

“Throw it AWAY? A striper? Shit.”

“Forget it. You don’t have to do anything. I will. Just tell me how.”

“Tell you how?”

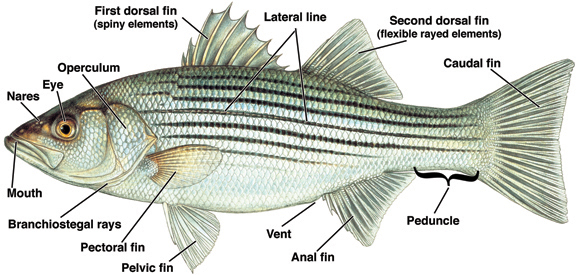

No problem, I taunted, all you need to do is remove the fins, scrape every single last scale of four square feet of fish skin, cut it from its gills to its anus and tug free a couple-three handfuls of icy cold fish guts. Oh, and then clean the god forsaken mess up before even turning on the stove. All at 6:30 on a Sunday. With that I stormed into the garage, found a ten-penny nail and a framing hammer, grabbed the fish (sure enough it had the tin tag looped from gob to gill vent) from on top of the cooler.

“Nice fish,” I said, impressed.

“I told you,” said Lisa.

I nailed the fish’s tail to the fence, turned to Lisa who was cold, and heading back inside. “No way. If I’m going to process this fish in the dark, you’re holding the flashlight.”

After some to-do I recovered two respectable fillets. After pawning off the guts and carcass on the chickens, I picked what remained of the broad leaves from the spindly fig tree and washed my hands and the leaves thoroughly. I sliced the fillets into single-serving pieces and then placed alternating layers–fig leaves, seasoned fish, olive oil–until the baking dish was full. The fish baked at a high heat to draw out the flavor and aroma from the fig leaves. I served it all with baked spaghetti squash seasoned with Chinese Five Spice (fennel, cloves, and cinnamon, star anise and Szechuan peppercorns) and steamed broccoli. (7 servings in 50 minutes, not including fish processing)

Tag Archives: city chicken

What are you doing for lunch this Wednesday?

Yet Another Simple Farmer finds Himself Interviewed on NPR

The Only Real-Time Evidence of Life On The Farm

A Love Story, In No Way A Cautionary Tale

Featured

On Sale at Book-Sellers Nationwide and on-line

On Sale at Book-Sellers Nationwide and on-line

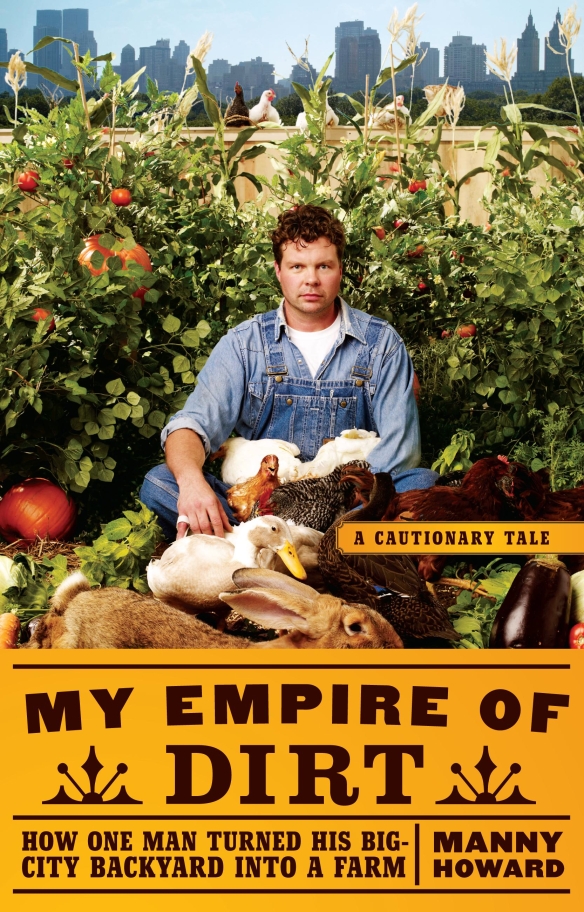

For seven months, Manny Howard—a lifelong urbanite—woke up every morning and ventured into his eight-hundred-square-foot backyard to maintain the first farm in Flatbush, Brooklyn, in generations. His goal was simple: to subsist on what he could produce on this farm, and only this farm, for at least a month. The project came at a time in Manny’s life when he most needed it—even if his family, and especially his wife, seemingly did not. But a farmer’s life, he discovered—after a string of catastrophes, including a tornado, countless animal deaths (natural, accidental, and inflicted), and even a severed finger—is not an easy one. And it can be just as hard on those he shares it with.

We now think more about what we eat than ever before, buying organic for our health and local for the environment, often making those decisions into political statements in the process. My Empire of Dirt is a ground-level examination—trenchant, touching, and outrageous—of the cultural reflex to control one of the most elemental aspects of our lives: feeding ourselves.

Unlike most foodies with a farm fetish, Manny didn’t put on overalls with much of a philosophy in mind, save a healthy dose of skepticism about some of the more doctrinaire tendencies of locavores. He did not set out to grow all of his own food because he thought it was the right thing to do or because he thought the rest of us should do the same. Rather, he did it because he was just crazy enough to want to find out how hard it would actually be to take on a challenge based on a radical interpretation of a trendy (if well-meaning) idea and see if he could rise to the occasion.